Geography

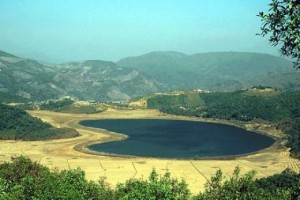

Chin State is located in the southern part of northwestern Burma (Myanmar), bordered by Bangladesh and India to the west, Rakhine State to the south, and Magwe and Sagaing Divisions to the east. The entire state is about 14,400 square miles. Chin State is also known as the “Chin Hills” due to its mountainous geography that has an average elevation of 5000-8000 feet. The highest peak is Mt. Victoria that rises 10,017 ft. above sea level (Center for Applied Linguistics, 2007).

The land is rich in natural resources that are primarily forest based, and the climate includes three main seasons: summer (hot), winter (mild), and rainy (wet). April and May are the warmest months of the year, with temperatures reaching 90 degrees Fahrenheit. Most Chins live at higher elevations in the Chin Hills. The capital, Hakha, lies at approximately 6000 ft. above sea level. The Chin people live primarily in Chin State, but also inhabit areas of the Chittagong Hills tract of Bangladesh, and in Mizoram and Manipur states of India (Center for Applied Linguistics, 2007 and Karen Human Rights Group & Open Society Burma Project, 1998).

History and Politics

The British first conquered Burma in 1824, established rule in 1886, and remained in power until Burma’s independence in 1948. The 1886 Chin Hills Regulation Act stated that the British would govern the Chins separately from the rest of Burma, which allowed for traditional Chin chiefs to remain in power while Britain was still allotted power via indirect rule (Human Rights Watch, 2009). Burma’s independence from Britain in 1948 coincided with the Chin people adopting a democratic government rather than continuing its traditional rule of chiefs. Chin National Day is celebrated on February 20, the day that marks the transition from traditional to democratic rule in Chin State (Center for Applied Linguistics, 2007).

The new-found democracy of Chin State ended abruptly in 1962 with the onset of the military rule of General Ne Win in Burma (Center for Applied Linguistics, 2007). Ne Win remained in power until 1988 when nationwide protests against military rule erupted. These uprisings, commonly known as the 8-8-88 because of the date on which they occurred, were met by an outburst of violence by the military government. The violent government response killed approximately 3,000 people in just a matter of weeks and imprisoned many more (Human Rights Watch, 2009). It was during this period of resistance to military rule, that the Chin National Front (CNF) and its armed branch, the Chin National Army (CNA), gained momentum (Human Rights Watch, 2009).

In 1990, the National League for Democracy (NLD) won multiparty legislative elections in Burma. Despite the grand win of the NLD, the military government refused to step down from power. The leader of the NLD and subsequent Noble Peace Prize recipient, Aung San Suu Kyi, was first placed under house arrest from 1989-1995 and again from 2000-2002. She was imprisoned in May 2003, and then placed once again under house arrest where she continues to remain today (CIA World Factbook, 2009).

In present day Burma, the Chin National Front (CNF) and Chin National Army (CNA) are not a threat to the government’s armed forces, or “Tatmadaw.” There are ongoing small-scale conflicts between the CNA and Tatmadaw, but the CNA are consistently outnumbered (Human Rights Watch, 2009). It must be noted, that within the Chin group, divisions between Chin sub-tribes have historically been present and continue to exist in the present-day. In present day Burma, the Chins are heavily abused by the Tatmadaw (Burmese Army). These abuses include extrajudicial killings, arbitrary arrest, detention, torture, forced labor, religious repression, restrictions on movement, forced military training and conscription, and sexual harassment and violence (Human Rights Watch, 2009).

Refugee Situation

It is estimated that at least 60,000 Chin refugees are living in India while more than 20,000 Chin refugees are living in Malaysia. Several thousands more are scattered in North America, Europe, Australia and New Zealand (Chin Human Rights Organization, 2010).

The majority of Chin refugees entering the United States and coming to Seattle are Christians who are either young, single males or young couples (20-40 years old), some with children. Most are uneducated and come from villages. Many are pushed to leave by their parents for fear that they will be forced by the government to take part in dangerous or difficult jobs that range from road paving to human mine sweeping – it has been documented that civilians forced to porter in Burma’s conflict areas are sometimes sent before the troops so that they will detonate mines (Online Burma/Myanmar Library, 2010). The government is known to treat ethnic groups and non-Buddhists more harshly than the predominant Burman ethnic group (68%) and Buddhists (89%) (CIA World Factbook, 2009). “The Chins are a double minority” explained one refugee interviewed for this profile. Because of this discrimination, some Chin refugees may not want to be called Burmese.

The Chins who flee Burma usually enter the United States directly from Thailand, Malaysia, and India. For most leaving Burma, the trip is illegal, dangerous, and expensive. There are brokers involved who charge approximately $1000 per person to transport refugees across the border. If those fleeing are caught by either the Burmese government or the government of the country they are trying to enter, they face imprisonment that may include harsh treatment such as being beaten. Those in refugee camps (located mainly in Thailand) are told that it will be easier to gain entry into the United States if they have children, thus many young, new parents (sometimes still in their teen years) are entering the United States and need jobs immediately in order to support their young families.

Employment in U.S.

Chins are quite gender conscious regarding employment, thus certain jobs such as housekeeping are considered “women’s work” and a man would not consider such employment. In the Midwestern states, a common job for Chin refugees is working in the slaughterhouses. Heavy labor is not a desirable job, as many Chins tend to be small in stature. Thus, jobs such as carpentry and cooking are much more desirable.

Language

There are about twenty to twenty-five dialects of the Chin languages. Of these, the most widely spoken are: Tedim among Northern Chin; Hakha and Falam among Central Chin; and Mindat Cho among Southern Chin. (CAL, 2007) Each dialect is so distinct that people who speak different dialects will not likely understand each other. While the Chin languages are those spoken primarily by the Chin people, about 80% of Chin refugees in the Seattle area also speak Burmese. Chin patients who speak Burmese are happy to receive interpretation in the Burmese language if an interpreter who speaks their Chin dialect is not available.

Names and Naming

The Chin people do not have a first, middle, or last name as is common in Western countries, but rather one name that may reflect the achievements of a grandparent or the grandparents’ future wishes for the child (Center for Applied Linguistics, 2007). The naming of a child is considered very important among the Chins and this honor is given to the grandparents. Parents of children who are born in the United States may appreciate an explanation that in the U.S., children are given names (both first and last) immediately at birth and there is no waiting period.

Greetings

A gentle handshake is a common greeting in Chin culture.

National Symbol

Hornbill, Mythun or Gayal, and Rhododendron are national symbols of the Chins.

Body Language and Displays of Respect

Among the Chin people, direct eye contact is sometimes viewed as an act of challenge rather than a sign of attentiveness and politeness. Thus, when having a conversation, most Chin will not look the speaker directly in the eye. When elders are present, the following actions are common signs of respect: walking with the body bent at the waist, crossing both arms over the chest, sitting at a lower level than the elders, and not pointing feet at the elders (Center for Applied Linguistics, 2007). Pointing feet at anyone is a sign of disrespect.

Marriage, Family, Kinship and Gender

The majority of marriages among Chins are not arranged, though parental approval is sought. Wedding ceremonies are considered very large events and the entire village may be invited. People tend to marry young, with most women being married by the age of 25. In the Chin Hills it is quite common for couples to have four to six children. Children are considered to be one’s future.

In the Chin Hills, the husband is considered the head of the household, the decision maker, and breadwinner. Women are expected to do all of the housekeeping including cooking and tending to the children in addition to working in the fields. Once the family moves to the United States, both parents tend to work and provide for the family. However, despite both parents being in the workforce, it is still common practice among Chin refugees here in the U.S. to think of household chores as “woman’s work” and thus leave such tasks to the woman.

Pregnancy and Childbirth

In the rural areas of the Chin Hills, midwives assist women in childbirth. In rural areas, childbirth is not viewed as a difficult task, but rather as simply another task a woman must accomplish. In urban areas, women commonly give birth in hospitals.

After giving birth, mothers in Burma traditionally drink oxtail soup or chicken soup to increase milk production. This practice continues in the Seattle area.

Contraception

Exposure to contraception varies among Chins entering the United States. In Burma, sex education is non-existent. A Seattle area physician who is Chin has suggested that Chin families space their children farther apart to improve health outcomes for mother and child.

Childhood and Socialization

Much of the child-rearing philosophy of parents is dependent upon how educated the parents are. However, one universal aspect of child rearing among the Chin people is that respect for elders is of utmost importance. The notion of “children are seen and not heard” is still common among Chins.

Boys are raised to be strong and tough, so adult men can sometimes seem cold, unemotional, and unexpressive. Girls are raised to be nurturing and to obey their husbands.

Old Age

In the Chin Hills it is common for the younger generation of the family to care for the elderly. Due to the exodus of many of the younger generation from Burma, care is not available for many elders. In many villages today, one sees very young children and the elderly.

Nutrition and Food

The staple foods for the Chins in Burma are rice, corn, and millet. In the U.S. the staple is rice. Rice is eaten at every meal, usually with vegetables and meat. White rice is preferred by the refugee community as the brown rice in the U.S. is not considered as tasty as the brown rice grown at home in Burma. Additionally, brown rice is less desirable because the grain is not polished. Meat is typically boiled with vegetables (mustard greens or cabbage) or fried with oil. The typical ingredients used by Chins for their meals are available in most Asian food markets in the United States.

Drinks, Drugs and Indulgences

Alcohol abuse is common among male Chin refugees in Seattle. In the Chin Hills, the traditional alcohol, zu, is seen as a status symbol and is not as easily accessible as alcohol is in the United States. Zu is homemade and provided at village feasts and celebrations, and the symbolic nature of zu is clearly portrayed by the custom of only allowing the male with the highest status to take the first drink at a gathering. In the United States, Chins are surprised to find that alcohol (specifically beer) is easily available for purchase, “cheaper than water,” and thus becoming easily abused.

Another type of substance abuse among the Chin people is tobacco. As with alcohol consumption, smoking is seen as a status symbol, and thus if affordable, many will end up smoking simply because it is viewed as a sign of wealth. In the Chin Hills, the traditional means of “smoking” is through the use of nicotine juice called thibur. Thibur is primarily used by the elderly, who hold the juice in their mouths and eventually spit it out. The elderly carry thibur in containers made from small gourds. Children are expected to prepare the thibur for the elders. To create thibur, nicotine is smoked in a water pipe which produces thibur drippings. This practice is not done in the United States.

Religious Beliefs and Practices

Christian missionaries first arrived in Chin State in the late 1800’s. The majority of Chins today are Christians, with most belonging to Protestant denominations, especially Baptist. Among the Chin refugees arriving in the United States, almost all are Christian (Center for Applied Linguistics, 2007). There are still a few Chins who practice traditional animism. They believe that both good and bad spirits live in high trees and mountains, and that the bad spirits are capable of hurting people and thus must be appeased (Center for Applied Linguistics, 2007).

Death

Chins provide a Christian funeral and burial for their dead. In the Chin Hills, there are no funeral homes, so the body will be wrapped in a traditional Chin blanket or puan and placed on a bed in the family home for one to three days. During this time, the family will receive visitors who come to pay their respects. Those who knew the deceased will sing funeral dirges, which focus on the achievements of the individual. After this waiting period, the body will be taken to the cemetery and given a burial ceremony (Center for Applied Linguistics, 2007).

Traditional Medical Practices

Many Chin people partake in the traditional practices of “coining” and “cupping.” Coining involves first rubbing heated oil on the skin and then rubbing a coin over the skin until a red mark is seen. This practice is meant to release the “bad” from the body; this “bad” is thought to be the cause of the patient’s illness. Coining is commonly used for treating less serious illnesses such as cough, headache or fever; however, the results of coining may be quite serious. Coining has been reported to cause burns and bruises. Parents will sometimes use this treatment on their children and may be at risk of subsequently being accused of child abuse (Creighton University School of Medicine, 2005). Cupping is an ancient Chinese practice that involves placing a cup over the skin and using fire or suction to create a vacuum within the cup which draws the skin and superficial muscle layer into the cup (Creighton University School of Medicine, 2007). It can leave marks on the body and there is a small risk of burns or swelling (American Cancer Society, 2008).

When a child is ill, a parent may bind the finger or the tongue and prick the skin to release a small amount of “bad blood” to cure illness.

No comments:

Post a Comment